Fiduciary Duty Of Boards: When Bad Things Happen To Good Public Accounting Firms

Recent events point to the need to reexamine the Fiduciary Duty of Boards.

Wirecard AG, headquartered in Munich, Germany, is a large, international payments processing fintech company. On June 19th, the Wall Street Journal reported that funds totaling approximately $2.1 Billion appeared to be missing from accounts held in trust for the firm’s third party partners operating in countries where it is not licensed to operate. That disclosure followed a report issued in April by KPMG, which had been commissioned by Wirecard to investigate anonymous claims of impropriety. The KPMG report, in turn, caused Wirecard’s auditor since 2009, Ernst & Young GmbH, to demur in its opinion as to the accuracy of the firm’s financial statements. Since then, Wirecard’s CEO resigned, then was arrested, its COO is sought by German and Philippine authorities, the firm entered bankruptcy since roughly 25% of its reported assets were missing (if they ever, in fact, existed), and EY is under fire for not uncovering the alleged fraud during its 10-year tenure. This story is unfolding on a near-daily basis, but is eerily reminiscent of the largest fraud I personally investigated: Phar-Mor, Inc.

Founded in 1982 by Michael (Mickey) Monus, and headquartered in Youngstown, Ohio, Phar-Mor failed in 1992, when fraud totaling $1.1 Billion was discovered. The firm had touted its revolutionizing of discount drug stores by adding home goods, some sporting goods, and health and beauty products; pretty much what CVS and Walgreens are today. It grew exponentially, rising to 300 stores staffed by 25,000 employees in 34 states, with $1.5 Billion in annual sales. Monus was a charismatic man who was lionized in Youngstown. He was chairman of the Board of Trustees of Youngstown State University. A sports fanatic, he founded the short-lived World Basketball League and was part of the group that purchased the Colorado Rockies baseball team. I became involved because a bank purchased by my employer had financed strip shopping centers anchored by Phar-Mor stores. Following his conviction in federal court, Monus was sentenced to 19 years, seven months in federal prison; later reduced to 10 years, which he served. The firm’s auditor was Coopers & Lybrand. The investigation and prosecution of Monus and Phar-Mor’s CFO revealed that Coopers had routinely told management in advance of when a store would be inventoried. That foreknowledge was crucial to the perpetuation of the fraud, since $650 Million of the $1.1 Billion was represented by overstated inventories. Phar-Mor trucks would be loaded at already-inventoried stores, then unloaded at about-to-be inventoried stores. Coopers was successfully sued by several investors for failing to follow Generally Accepted Auditing Principles and subsequently merged with PriceWaterhouse.

Then there’s Enron, whose spectacular failure (after WorldCom, Adelphia and Tyco, et al) spawned Sarbanes Oxley and killed Andersen Accounting. In the aftermath, it was revealed that the Andersen engagement partner had reviewed and approved the work of Enron’s chief accounting officer, who was a former Andersen colleague. The partner was subsequently prosecuted for obstruction of justice for ordering the shredding of subpoenaed documents. Another direct result was the establishment of Statement on Auditing Standards 99, Consideration of Fraud. SAS 99 stresses the importance of auditors to maintain a healthy professional skepticism throughout the audit process. Team members are also required to discuss how fraud might be committed. Or, as I emphasized to my staffs and my Masters students throughout my banking and teaching careers, think like a thief.

Fraud is an eternal verité. By definition it is done surreptitiously. And people with the right mix of need and inclination will always exploit any perceived opportunity to steal. My personal definition of fraud is how one answers the question “does this make sense”? If the answer is “yes”, then it’s more likely than not legitimate. A “no” answer calls for more scrutiny. During my banking career designing and managing fraud detection systems, I came to realize that looking for a needle in a haystack is relatively easy. Detecting fraudulent activity is like looking for a needle in a needlestack.

Since a fraud incident represents an internal control failure, firms must establish resilient internal control frameworks to reduce their risk. That’s why, in my opinion, the most potentially effective element of Sarbanes Oxley is §404(b), requiring the external auditor to attest to, and report on, management’s assessment of the company’s internal controls and procedures for financial reporting, particularly when combined with the auditor’s compliance with SAS 99.

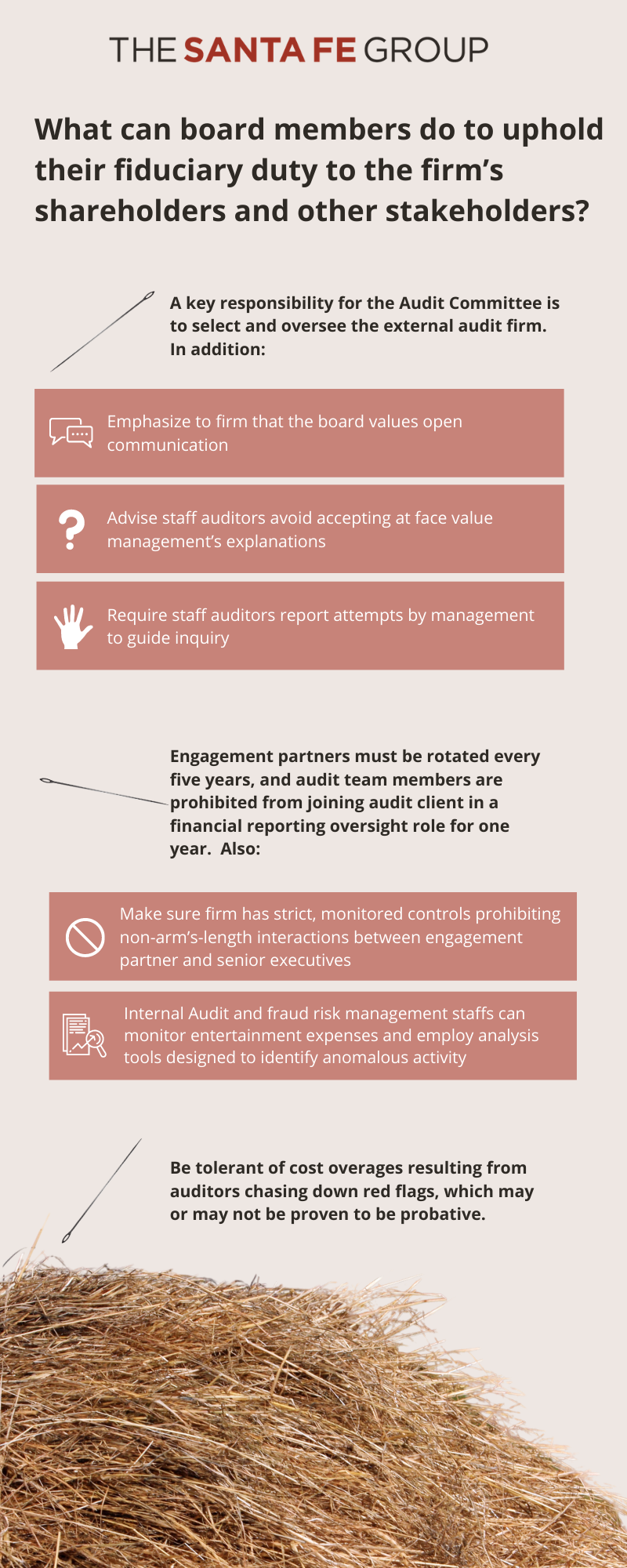

But what happens when the auditor loses that professional skepticism? Can it cause him to inform management in advance of a “surprise” inventory? Or favorably review the financial statements provided by his former colleague, while at the same time negotiating a management position for himself? What can board members, especially members of the board’s Audit Committee, do to uphold their fiduciary duty to the firm’s shareholders and other stakeholders? I suggest three things:

1.One of the most important roles of the Audit Committee is to select and oversee the external audit firm. In my opinion, time spent during executive session stressing with the engagement partner the value the board places on frank, unvarnished communication is well spent. So, too, demanding that staff auditors, particularly those new to the field, be admonished to avoid accepting at face value management’s explanations, and be directed to report any attempts by management to guide their inquiry or intimidate them.

2. Even though, post-Enron, engagement partners must be rotated every five years, and audit team members are prohibited from joining the audit client in a financial reporting oversight role for one year; make sure the firm has strict, monitored controls prohibiting any non-arm’s-length interactions between the engagement partner and senior executives. The Internal Audit and fraud risk management staffs can be helpful here in monitoring entertainment expenses and employing monitoring and analysis tools designed to identify anomalous activity.

3. Be tolerant of cost overages resulting from auditors chasing down red flags, which may or may not be proven to be probative. They just might have found the right needle.